Early in their development, videogames started integrating influences from the film and television industries. It was natural because videogames share with them all the audiovisual elements, even when the gaming experience and the illusion of player’s choice is what sets them apart. However, in their attempt to achieve artistic autonomy, narrative videogames seeking to tell stories of their own, and represent the hero’s journey in their own fashion, found themselves with the difficulty of separating themselves from the art of filmmaking.

As Brett Martin put it in the piece he wrote for Videogames and Art (Clarke and Mitchell: 2007), “Stylistically, cinema is the closest medium to videogames. Both rely heavily on technological advancement to draw crowds and are entrenched in the commercialistic world.” But he added further that “movies today have more to offer aesthetically than games, and until games establish themselves apart from movies they will not be considered art.” This has led critics to declare that, even though they can contain art, in themselves videogames are not a legitimate form of art.

Game Developer Joseph D. Kucan as Command & Conquer’s main villain

Starting in the 90s, most narrative videogames were, in many ways, movies where the player took decisions, but movies nonetheless. There were videogames that not only started hiring actors to interpret their characters’ voices, but that filmed their actors in dramatic cinematics inserted between gameplay, like with the Command & Conquer (1995) series, Jedi Knight: Dark Forces 2 (1997) and Star Trek: Klingon Academy (2000), reaffirming the influence coming from cinema. Most remarkably, Metal Gear Solid (1998) offered a passionate plot full of complex characters, and a thrilling action adventure narrative divided in three acts like a motion picture screenplay, in its attempt at presenting the artistic rigor of filmmaking. These proposals not only aimed at introducing the player in a playful experience disguised by any narrative motive whatsoever, but they turned the story plot into what was being played. But being movie-like didn’t convince the critics. On the contrary, it made many declare that the art is loaned from outside the medium, but not an integral element of it.

Actor Christopher Plummer interpreting General Chang in Star Trek Klingon Academy

For instance, in 2021, Darren Allen goes as far as declaring that the videogames’ purported addictive component and lack of truth-contemplation for its own sake make them more akin to pornography. “This doesn’t mean that videogames can’t contain art. What if, for example, Deus Ex used Mozart’s Requiem as its score? Does that make it art? Obviously not, no more than if someone stuck a Van Gogh in Tracy Emin’s tent. Or what if Fallout contains some neat satirical posters and a bit of (rather crude) social commentary, does that make the game art? No more than if a director of hardcore porn had one of his actresses recite a haiku.” It is this feeling that artistic elements are loaned from outside the medium that makes critics doubt, if not outright reject, that videogames can ever achieve artistic virtue.

But why did videogames ever enter this debate in the first place? From the very start, videogame developers hired artists into their projects, especially illustrators as concept artists as well as musicians. But something changed in the mid 90s, when they shifted from using these arts as secondary elements, to trying to reproduce the film industry’s narrative complexity, sophisticated visuals and emotional musicalization. Even when there were exceptions in which games attempted to be artistic products on their own right without reference to filmmaking, like with Little Big Adventure 2: Twinsen’s Odyssey, these cases were rare. Which brings us to the question of whether videogames are only games, or if they can be considered an art form in themselves.

Little Big Adventure 2: Twinsen’s Odyssey’s gameplay

Back in 2012, when New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) decided to include a set of videogames as part of its permanent collection, including pieces as old as Pong (1972) and as recent as Minecraft (2011), backlash by some cultural critics didn’t wait. Jonathan Jones wrote in The Guardian an article titled Sorry MoMA, video games are not art, and he argued that “the worlds created by electronic games are more like playgrounds where experience is created by the interaction between a player and a programme. The player cannot claim to impose a personal vision of life on the game, while the creator of the game has ceded that responsibility. No one “owns” the game, so there is no artist, and therefore no work of art,” a conclusion that led him to compare the medium more with board games as ancient as Chess, well respected but not considered art. Jones stresses the essential element the author plays when defining what is and what is not art: “Walk around the Museum of Modern Art, look at those masterpieces it holds by Picasso and Jackson Pollock, and what you are seeing is a series of personal visions. A work of art is one person’s reaction to life. Any definition of art that robs it of this inner response by a human creator is a worthless definition. Art may be made with a paintbrush or selected as a ready-made, but it has to be an act of personal imagination.”

The purported author’s lack of agency is something that Allen also uses as argument for only considering them an industry’s products rather than artists’ creations. “Video games are usually made by corporate committees. There is very rarely a single consciousness behind them. Not that art cannot come from groups of people working together (‘jamming’), but that system-embedded committees do not and cannot put artistic truth or beauty first, or do anything meaningful to discover an immortal expression of that truth. They have to put profit, popularity and system-approved convention first, they have to test and retest their games for popularity, for efficacy, for utility.”

Videogame designer and producer Kellee Santiago attempted answering these questions in a TED talk that steered some response. Titled An Argument for Game Artistry, she defended that all art forms develop from very rudimentary early stages, like prehistoric cave painting is to modern painting. She argues that videogames are, as of 2009, in their cave infancy, but nothing stops them from becoming full-bred art forms in the long future awaiting them. Martin makes a similar case by refreshing his readers memory regarding the uphill battle photography and cinema had to climb before being accepted as legitimate art forms as they are today. Nothing really stops videogames from gaining the same recognition. But beyond historical parallelisms, what are the specific arguments for considering videogames as a form of art?

Narrative Through Gameplay

The concept of narrative through gameplay has changed the way videogames are understood artistically, by elevating their content qua games and not as byproducts of filmmaking. This has developed through narrative elements linked to gameplay mechanics and user interactions, rather than relegating narrative to cinematics or written elements. In the 90s, most videogame stories progressed in cinematics, making the player a mere spectator of the plot before going back to gameplay. In Metal Gear Solid, the player accumulated hours of narrative as a spectator, a time lapse that could actually be longer than gameplay time overall. Developers have abandoned this narrow vision in favor of a much more dynamic perspective of gameplay narrative, where the player rarely loses control of the character.

Metal Gear Solid 2’s gameplay

Thanks to the development of physics engine technologies that reproduce real-life physical interactions, crowd systems that simulate people’s behaviors in public spaces, as well as NPC artificial intelligence that reacts in situ to the player’s choices, an infinitude of dynamic narrative possibilities are unchained and explored in recent videogames, unscripted situations that are unique to each player as he/she interacts with the world set up by developers. In this sense, we can claim that the playable element in itself has earned narrative significance, and in consequence, artistic value very much like performative arts where the artists interact with the viewers. And it’s only due to the interactive element of gameplay that its artistic component cannot be subsumed to filmmaking, nor to any other form of art.

The case for Level Art

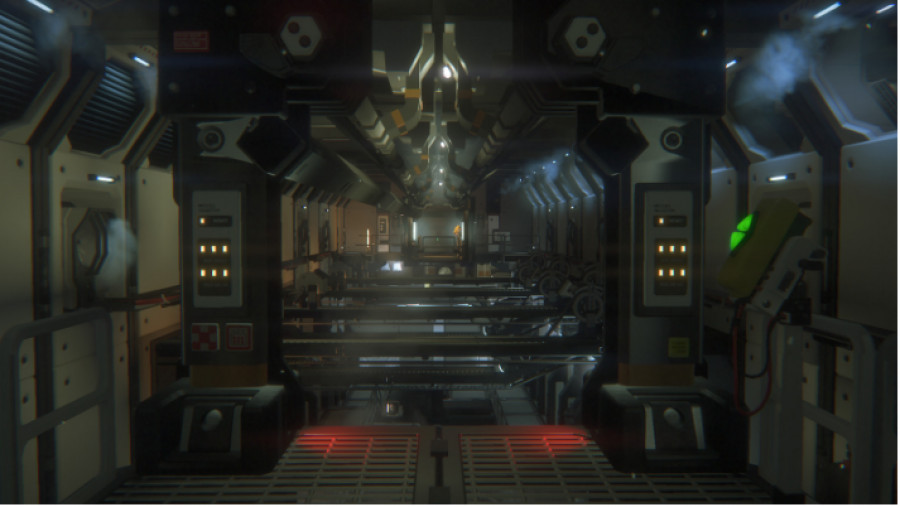

An aspect that has always been present in the industry, but that has acquired a more artistic significance in latter years has been Level Design. Level Design quickly gained an architectonic character, where the part of every level’s function fulfilled a playful as well as aesthetic purpose, in ways that plunged the player in fictional worlds, while at the same time presented him/her with the level’s challenges. It is no longer a mere placement of obstacles, but the art of designing level details and challenges to melt into the context in a way that’s also world building, similarly to how architecture builds worlds around us filled with meaning. For example, Alien Isolation (2014) excelled for its labyrinthine and multi-layered level design, filled with objects and landmarks in ways that both impeded the player from advancing rapidly, but at the same time offering multiple hiding places from the game’s mortal threat, while creating a chilling atmosphere that gave the game it’s terrifying and thrilling appearance, as well as multiple choices to cross the level through. Level Design has become so detailed, thorough and sophisticated as a tool to communicate atmosphere and emotion to the player, that its name is being replaced by that of Level Art, recognizing its artistic value for development teams, and it’s something that far transcends any other art form, again for its interactive properties.

Alien Isolation’s complex and engaging level art

Visual Sublimity

Finally, the rise of graphic power and the beauty of modern visuals has given us truly aesthetical accomplishments. The development in hardware capacity, solid hard drives, graphic cards, fourth generation RAM, added on top of breakthroughs in software engines, like Unreal 5, allow visual experiences very close to real life, or fantasies unimaginable a few years back.

Just as in cinema, the advancement of technology has allowed 3D modelers and animators to offer portrayals of human beings, human-like creatures and wildlife to an extent in beauty and complexity that it would be pitiful to disregard as non artistic. If the personal imprint each modeler and animator tries to give their characters –as would be thought of any sculptor– is not considered artistic, then what is it? Then there’s the awe-inspiring landscaping with Skyrim and so many other videogames after its revolutionary open world. This powerful element of world building is not reducible to a mere playground because of its interactive nature, just as people wouldn’t doubt the artistry of architecture just because it’s also interactive. For how can we describe the fact that we have to enter cathedrals and decide where to go and sit or stand, what windows or doors to open or close, if not interaction with the architect’s work of art?

Assassin’s Creed Origins’ spectacular recreation of Ancient Egypt

Having brought to the fore the three key artistic elements of narrative through gameplay, level art and visual sublimity, we can finally argue for videogames as a legitimate form of art. And with Santiago and Martin we can but accept that, as more artists join the industry and gain more influence in videogame projects, the medium will start to offer more works of art not reducible to mere games. Parallel to this development, a similar case in the United States was brought to the Supreme Court of Justice, where the court declared that figure skating is an art form rather than a sport, similar to the cases for ballet, synchronized swimming and parkour. The main argument stresses the beauty beholden in skating. The same can be said about videogames.

Even if there is a shadow of doubt that keeps the debate ongoing, in TagWizz we believe we speak for many other game developers when we say that creating a videogame demands the bringing together of artists and artistic visions into a single work. Notwithstanding that games focus on competition, as sports do, as Roger Ebert said in response to Santiago’s TED talk, we can’t deny the simple fact that many videogames are created by artistic minded people, with artistic drives, and a desire to offer aesthetic works for contemplation rather than competition. This simple fact informs our conviction that videogames are a growing art form.

This article was written by Adrian Gimate-Welsh with the help of TagWizz’s group of experts.